Enas Satir: touched by something true

This blog isn’t primarily designed to be politically topical; instead it is more a way of giving me a way to structure my research different artists and areas of interest within the planning of the exhibition. However, sometimes the stars align and a post ends up being very timely. October is Black History Month in the UK and I had planned to do a feature on Sudanese artist Enas Satir, which is now even more pertinent: last Saturday, 3rd October, the Sudanese transitional government and the Sudanese Revolutionary Front signed a peace agreement aimed at resolving years of war.

“When I made projects coming from being discriminated against due to my skin tone or my hair in my own country, being a woman, being Sudanese, being a Sudanese living in Toronto… my work usually has a point of view, so it is considered political, but it [also] comes from true experience and incidents that shaped my life.”1

South Sudan's secession from Sudan in 2011 came after more than 30 years of civil war between a mainly Arab, Muslim north and a mainly African, Christian south. The split further polarised those Muslim and Christian groups who remained in Sudan. Former president Omar al-Bashir's focus had been on establishing Arab supremacy, which side-lined many minority ethnic groups in Sudan, and the country's East African heritage. In December 2017, Sudanese across the world watched in disbelief as the government rolled out its plans for the 2018 budget, revealing that the vast majority of funds were earmarked for ‘defence and security’ – most of which went to the NISS, the national intelligence agency and main architects of oppression – while only 3% of the budget was set aside for education and 2% for healthcare.

By mid-2018, Sudan’s economic situation had deteriorated precipitously and then 19-year-old Noura Hussein was sentenced to death for killing the husband who had raped her and to whom she was married three years earlier by force, causing international outrage and plunging the nation once more into a debate on the legality of child marriage and marital rape. All of the resultant tension and anger prompted the people of Sudan to protest on the streets, with women on the frontlines of the nationwide uprising, resulting in the toppling of al-Bashir and the installation of the transitional government. Women’s actions on the ground were amplified by Sudanese women abroad, who joined the online mobilisation around the hashtag #SudanUprising, uploading blog posts, podcasts, and taking to social media from all around the world to broadcast constant reports, updates, photos, and videos of the situation in the country.

“We have to be the media; we live in the era of social media. We can be the media, spread the news, tell the people what is actually happening.”2

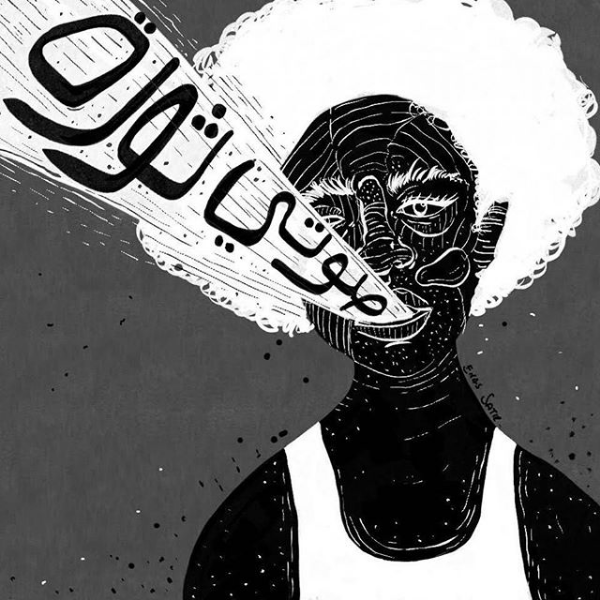

Key to the uprising’s dissemination of information during the revolution was art. Monochrome graphics and political revolutions are a combination that call to mind revolutions of the early 20th Century, the Russian and Chinese communist revolutions or the Spanish civil war, and looking at Satir’s graphic zines will make you realise this combination can still have considerable impact. Satir lives in Toronto but is still closely linked to her homeland, where she was heavily involved in the Sudanese revolution from an artistic standpoint; her illustrations portraying to non-Sudanese audiences why this revolution was happening and showing the Sudanese involved in the revolution the truths that were being repressed within the country.

"Art has been both 'healing' and energizing. When the protests broke out, I was overwhelmed with anxiety—being away from Sudan in times like these, when people are being killed and tortured and you're an ocean away, engulfs you with helplessness combined with a strange feeling of guilt."3

During the presidency of al-Bashir life was particularly difficult for women in Sudan. When a military coup brought al-Bashir to power in 1989, he imposed the Public Order Act, a set of ‘morality laws’ that had been oppressing women ever since. The Public Order Act took away a broad swathe of everyday rights from women in one fell swoop, from wearing trousers, to sitting in public places, all the way to smoking. The police widely would grab women they thought were ‘violating’ the act, bundle them into police cars, and then take them to a police station, where they would either be beaten or forced to pay bribes to be released. The revolution was a vehicle to fight against these repressions, to fight for women’s rights and against practices like female genital mutilation (FGM), child marriage, and unequal pay.

“Your story is always gonna be different and unique to you… sharing it with others will help them to identify with you, because they are touched by something they know is true, and not a fraction of your imagination.”4

Earlier this year Satir started producing ceramics in collaboration with Erin Candela, simple black and white domestic pieces featuring Satir’s stylised illustrated faces and speech bubbles in Arabic, very much an extension of her illustration practice, and highly effective objects for spreading Satir’s messages. ‘They arrested me, lashed me and I repented’ says one; ‘No thank you! I’ll find a man myself!’ says another. These are ceramics that confront the realities of oppressed women around the world head-on, the lone face putting me in mind of the ‘talking heads’ on 24-hour news channels, broadcasting Satir’s message in a totally different way to her illustration work. The cylindrical aspect of the mugs and tea bowls allow you to encounter just the face, almost like having a TV on mute, or just the text, which grabs you and makes you acknowledge the issue.

“… when it comes to ceramics, I do believe in letting go of my mind and rely on intuition. To me making ceramics, especially hand-built ceramics, you have to be very intuitive, so I need to tap into my intuition and what my hand tells the clay to do. As for the concept of Gonat itself: a lot of my art revolves around cultural issues and taboos, taboos that include discrimination or injustice or are essentially ugly.”5

These blog posts are published monthly, but if you want to access more exclusive content and to help my research, please consider supporting me on Patreon.

I also post photos daily to my Instagram profile.

1 – Enas Satir; The Satir Sisters: two artists inspiring change through illustration; 2019; published on https://shado-mag.com/do/the-satir-sisters-two-artists-inspiring-change-through-illustration/

2 – Enas Satir; Sudanese Women and The Making of a Revolution; 2019; published on https://www.nadja.co/2019/02/25/sudanese-women-and-the-making-of-a-revolution/

3 – Enas Satir; How Sudanese Art Is Fueling the Revolution; 2019; published on https://www.okayafrica.com/young-sudanese-art-is-fueling-the-protest-revolution/

4 – Enas Satir; The Satir Sisters: two artists inspiring change through illustration; 2019; published on https://shado-mag.com/do/the-satir-sisters-two-artists-inspiring-change-through-illustration/

5 – Enas Satir; email correspondence with the author; 2020

Edited by Sarah McGill

Enas Satir; Kezan and Why They Are Bad For You series; 2019 - “Mehira Bit Aboud, the Sudanese poet, in addressing Al Bacha (when Sudan was under his rule) ‘O, Simple-minded tyrant.. tell your dogs to git’. If she was alive today, would she use the same line of poetry against Al Kezan?”

Enas Satir; Illustration for International Women’s Day on Jeem.me; 2019

Enas Satir; Racism With Different Seasonings; 2020

Enas Satir; Gonat ceramics project; 2020

Enas Satir; No thank you! I’ll find a man myself!; 2020

Enas Satir; No thank you! I’ll find a man myself!; 2020

Enas Satir; They arrested me, lashed me and I repented; 2020